The Car and the Bicycle, Pt. 1 - Boston and the Invention of the Bicycle

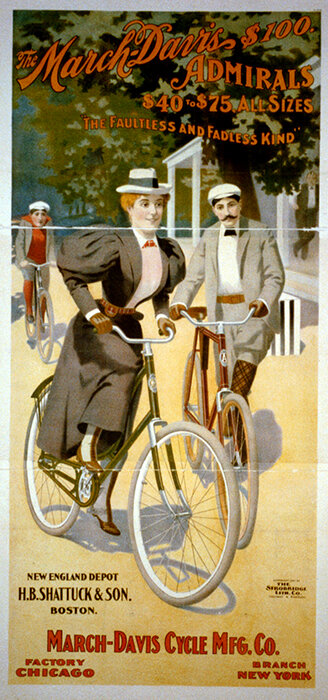

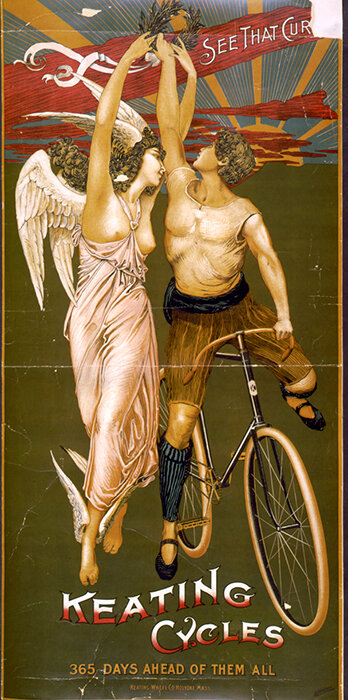

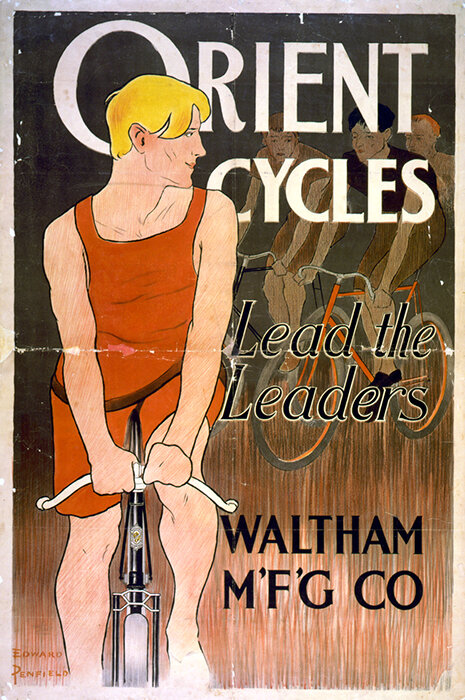

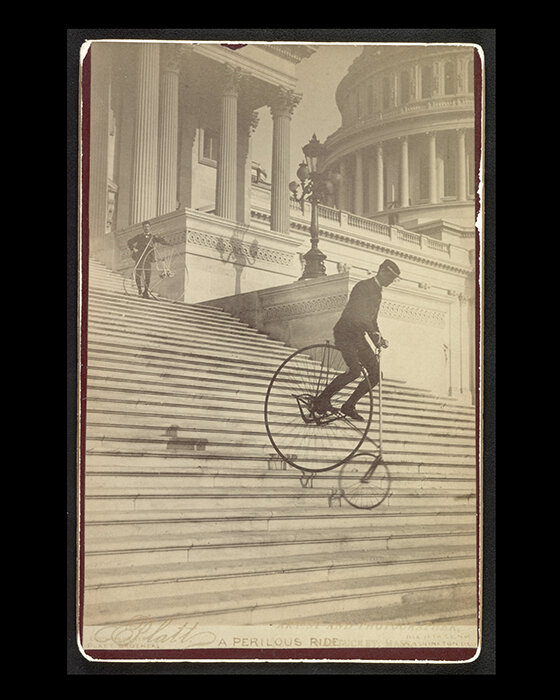

Source: Library of Congress

A Brief History of the Humble Two-Wheeler and the Boston Connection

By Edward Moran

Before the car dominated the Boston transportation scene, there was the humble bicycle. The velocipede, as it was called in the late 1800s, went through a golden age then declined after the rise of the automobile in the early 1900s. A resurgence in biking took place in the late 20th and early 21st century. Now the two modes of transport are locked in a head-to-head urban battle that is evident to all drivers in our area.

There is more to this story than simply describing dynamics of the battle and posting pictures of bike lanes. The history of two wheelers has its origins both in the Boston area as well as in Western Massachusetts. For this reason, a discussion of this topic will be split into three blog posts.

The history. The resurgence. The state of the modern day.

Forget about finding depictions of toga-clad bicyclists competing in the Roman Colosseum, or of armored cavalry riding their bikes into battle at Blenheim. The wheel may have been around since Neolithic, but its shotgun marriage with spokes, chains, and rubber tires had to wait another three millennia, until the Victorian era.

It has always puzzled me that bicycles evolved quite late on the technology time line. The first practical bicycles appeared only in the nineteenth century, decades after the invention of the steam engine and hot-air balloons and around the same few decades that railroads, automobiles, and even aircraft were making their debuts. (Let’s not forget the Wright Brothers started their flight experiments in their Dayton, Ohio bicycle shop. To their inventive minds, their work with “unstable” vehicles like bicycles helped them work out a practical method for stabilizing aircraft.)

Part of this, of course, can be blamed on the “rubber barons” who didn’t begin reaping the benefits of vulcanization until Charles Goodyear patented the process in 1860, allowing for the mass manufacture or reliable rubber tires. Part of it can be attributed to the general unavailability of standardized, factory-made gears and sprockets until the Civil War in America ramped up the nation’s technological know-how.

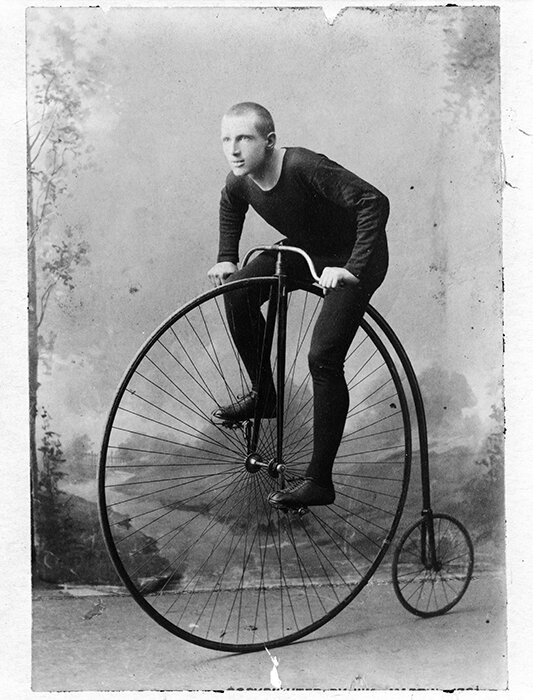

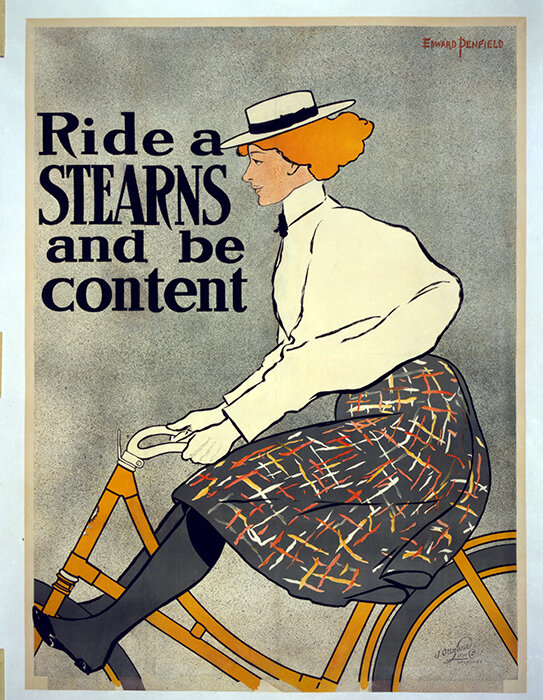

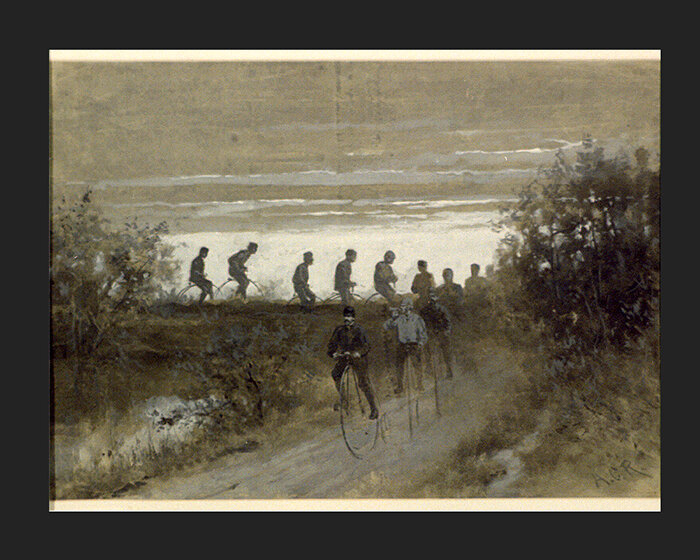

Source: Library of Congress

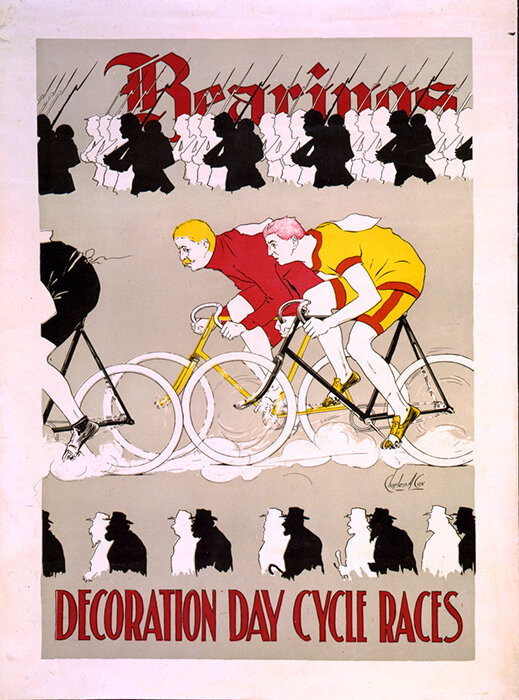

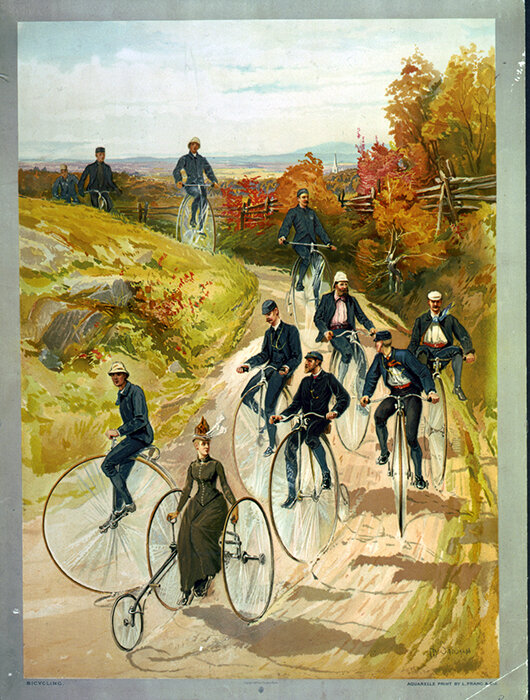

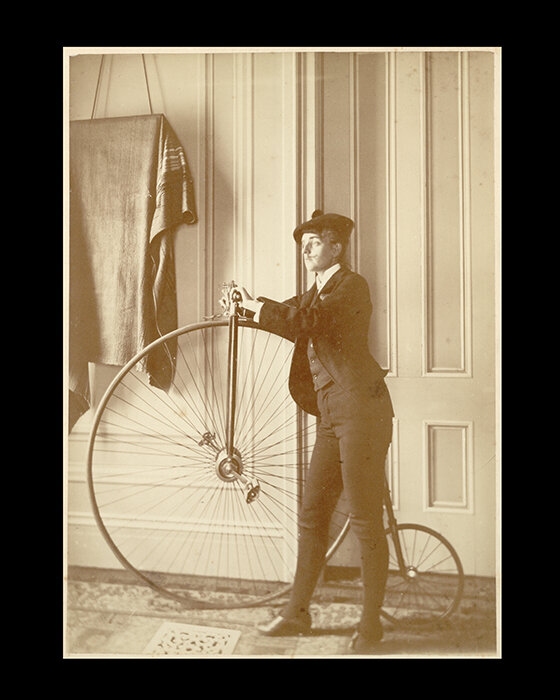

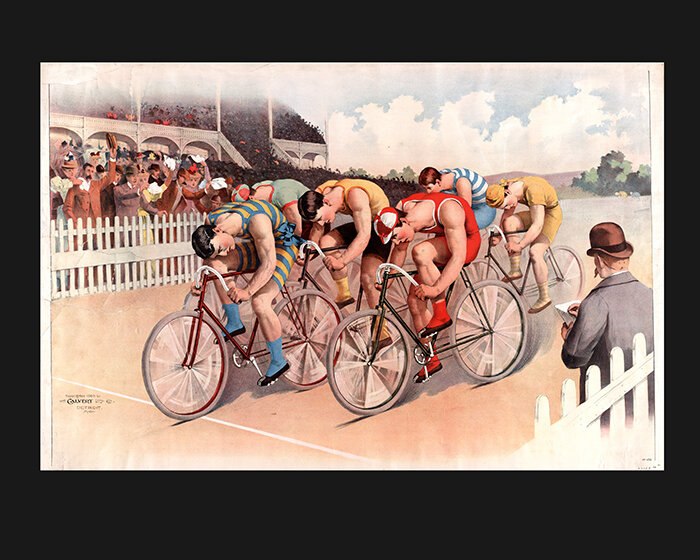

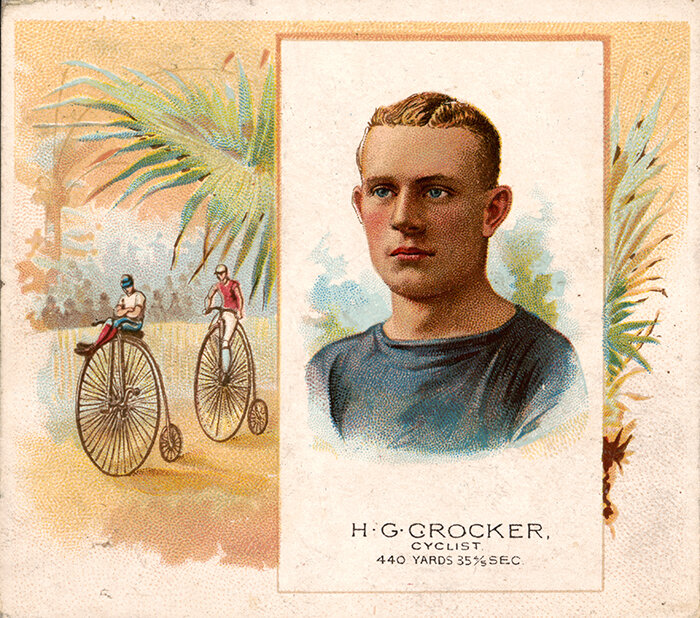

Though a few “dandy horses” and “bone-shaker” velocipedes appeared in Europe and in the British Isles as early as 1819, it was not until around 1880 that the bicycle as we know it today began to emerge. During the Gay Nineties, the bicycle of choice was still the “penny-farthing” variety: the kind you see in old prints with a rider perched five feet or more above the large front wheel. Penny-farthings helped usher in cycling as a sport, but they quickly vanished around the turn of the twentieth century with the development of the modern derailleur.

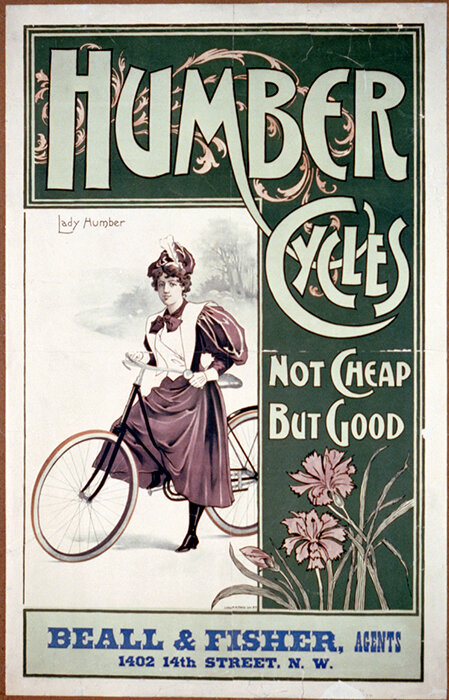

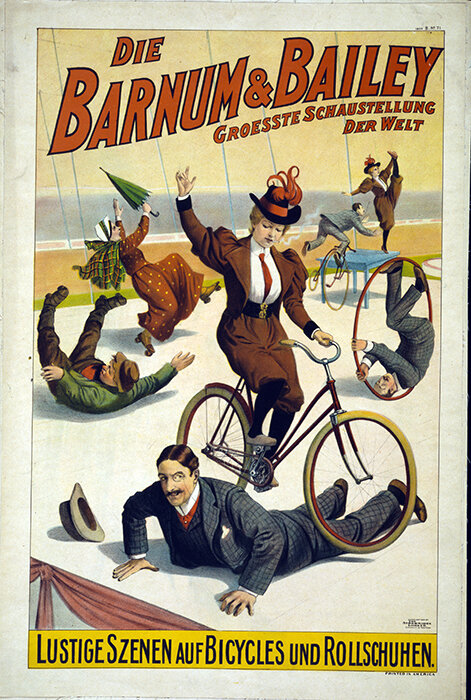

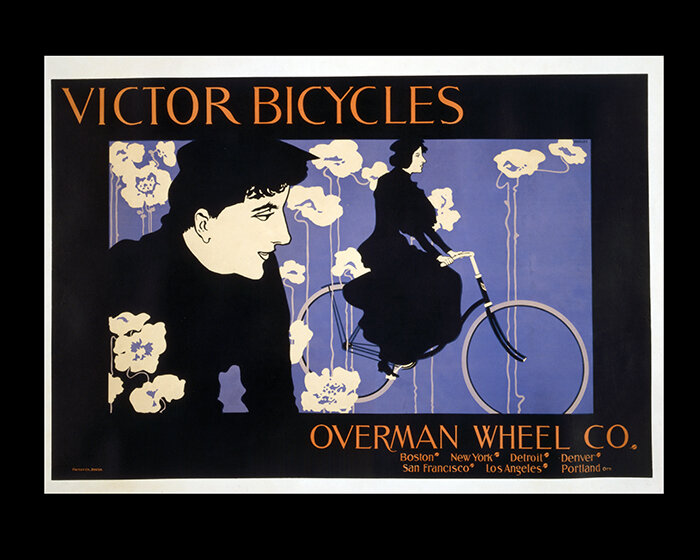

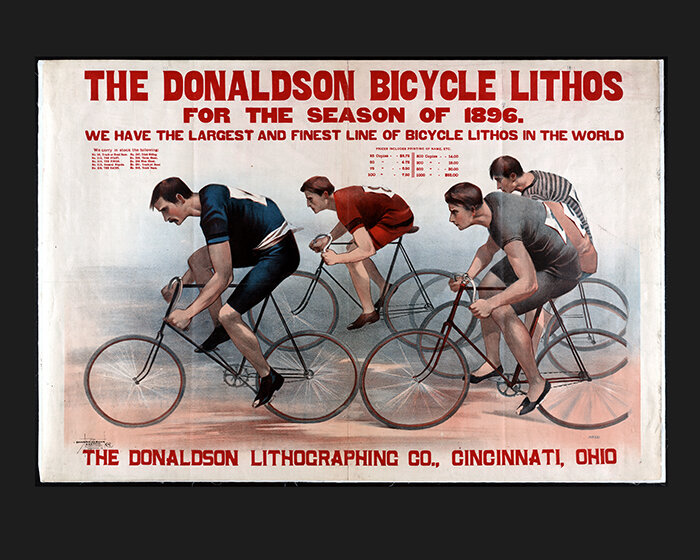

Back in the Gilded Age, entrepreneurs like William Witty in Brooklyn and Charles Pope in Brookline were among the first manufacturers to corner the market on the new bicycling craze, one that was jump-started by promotional maven P T Barnum who opened a velodrome in Jersey City, stocking it with 21 of the Witty cycles. “Velocipedes,” argued Barnum, “are superior to horses, they require no oats, little grooming and when the rider wishes to put away his machine, all he has to do is Barn-um.”

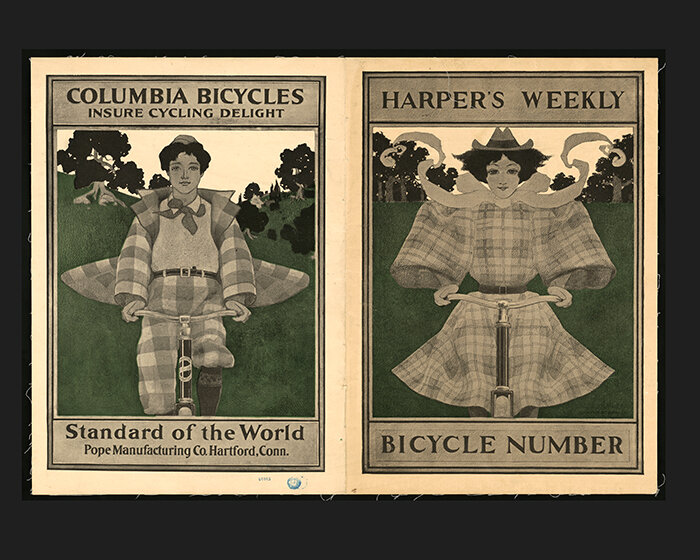

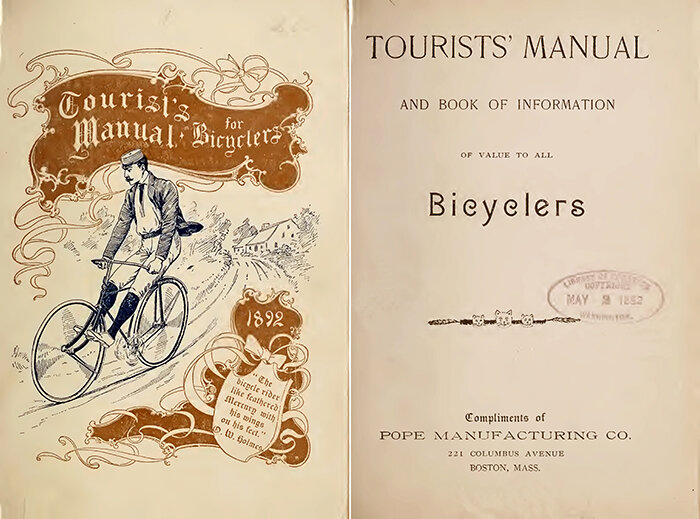

Another Boston-era entrepreneur who kick-started the bicycle craze in America was Albert Augustus Pope, who moved to Harvard Street in Brookline in 1846 and made a small fortune as a land developer in the newly growing suburb. Pope started importing English bicycles to the U.S. after he saw an exhibit at the 1876 Centennial exposition in Philadelphia. He then started manufacturing his own Columbia bicycles in Connecticut in the 1870s but soon moved his operations to Westfield, Massachusetts.

A ruthless tycoon who frequently sued his competitors for patent infringements, Pope was no stranger to civil disobedience: in 1880 he challenged the ban on bicycles in New York’s Central Park by promising to pay the fines of any cyclists arrested for the offense. He also was among the founders of the Massachusetts Bicycling Club and formed the League of American Wheelmen to lobby for better roads. Apparently, in Boston, that extended only to road surfaces, not to the twisted conglomeration of roadways and bizarre intersections that are today the bane of motorist and cyclist alike.

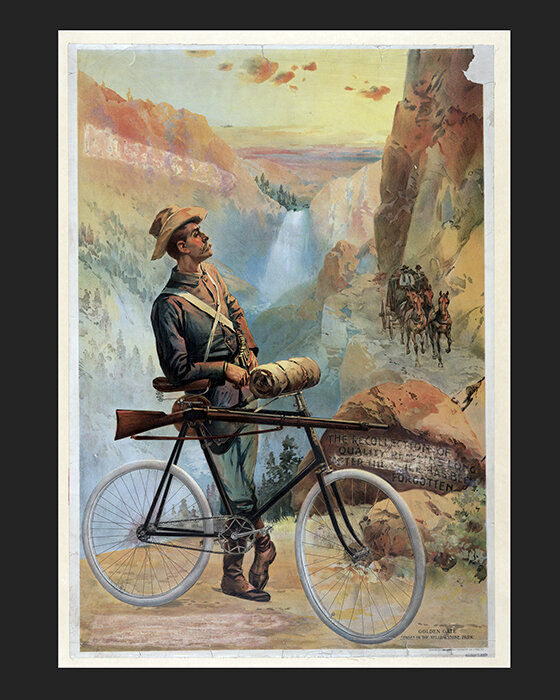

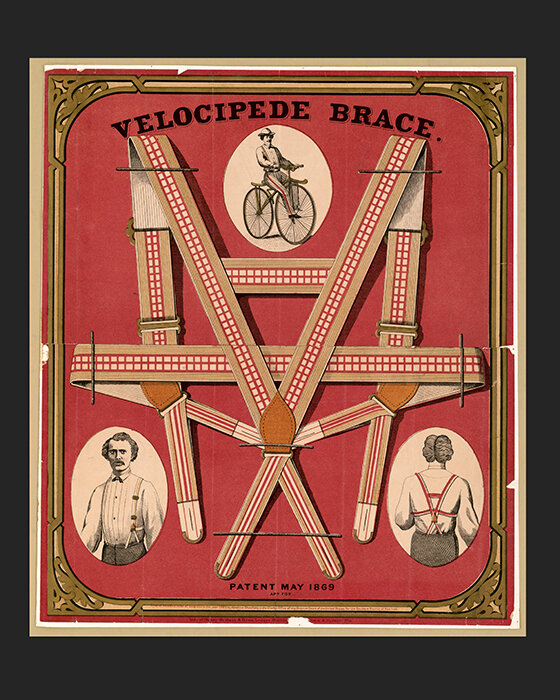

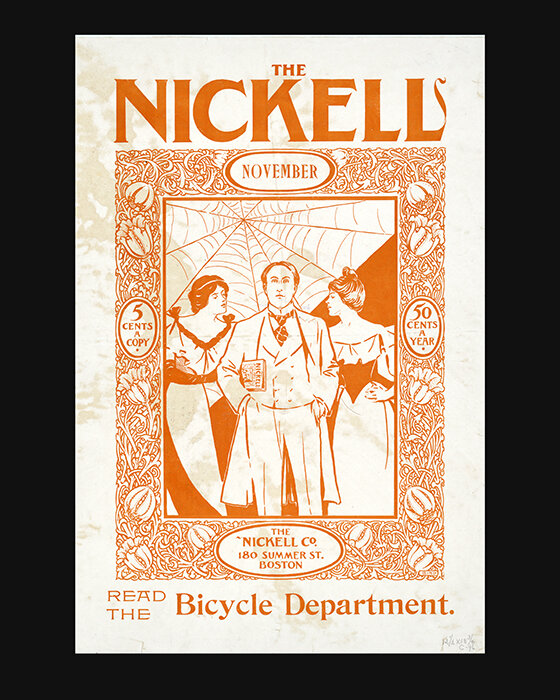

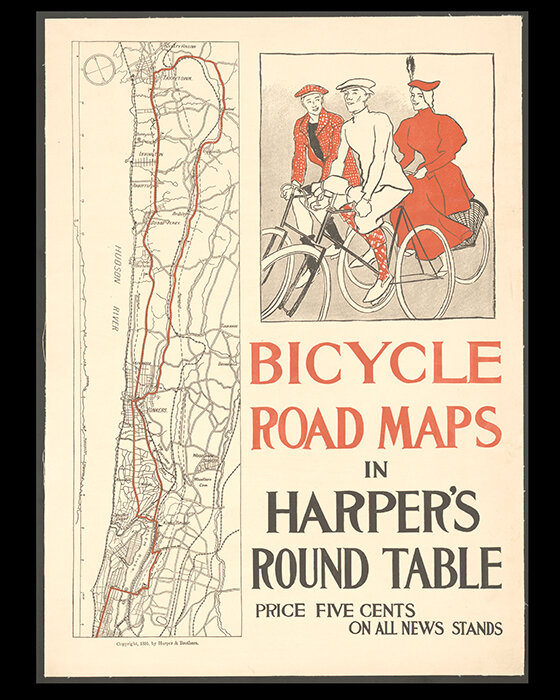

Source: Library of Congress

Boston played a significant role in American bicycling history, as attested by two recent books by Lorenz J Finison, both published by University of Massachusetts Press: Boston’s Twentieth-Century Biking Renaissance: Cultural Change on Two Wheels (2019) and Boston’s Cycling Craze, 1880-1990: A Story of Race, Sport, and Society (2014). On a more contemporary note, the City of Boston’s official website also includes a “cyclopedia” page of interest as well.

Yet another early bicycle promoter in the early 1900s was Carl G. Fisher, an Indianapolis cycle repairman and stunt man who once dropped a bicycle from the roof of a downtown office building to promote his business. He ultimately made his fortune selling headlights to the burgeoning automobile industry. He was one of the principals behind the storied Indianapolis Speedway but is perhaps best known for promoting what was once known as the transcontinental Lincoln Highway, an early precursor to today’s Interstate Highway System.

Bicycling enjoyed a brief heyday in the early 1900s, when the newly efficient two-wheelers were promoted as a way for city workers to commute to their jobs from newly constructed suburbs. But by the 1920s and the mass-production of automobiles—notably the Ford Model T—the bicycle quickly became a quaint anachronism in America’s love affair with the internal combustion engine.

You can’t quite imagine the Hells Angels furiously pedaling their Schwinns, can you?